MANILA, Philippines – The discussion on disaster risk reduction and management (DRRM) often focuses on supplying relief goods to the affected in the shortest possible time, or ways to mitigate the impact of disasters.

Psychiatrist Dr June Caridad Pagaduan-Lopez wants to add another aspect to the discussion: the mental health of traumatized victims of disasters.

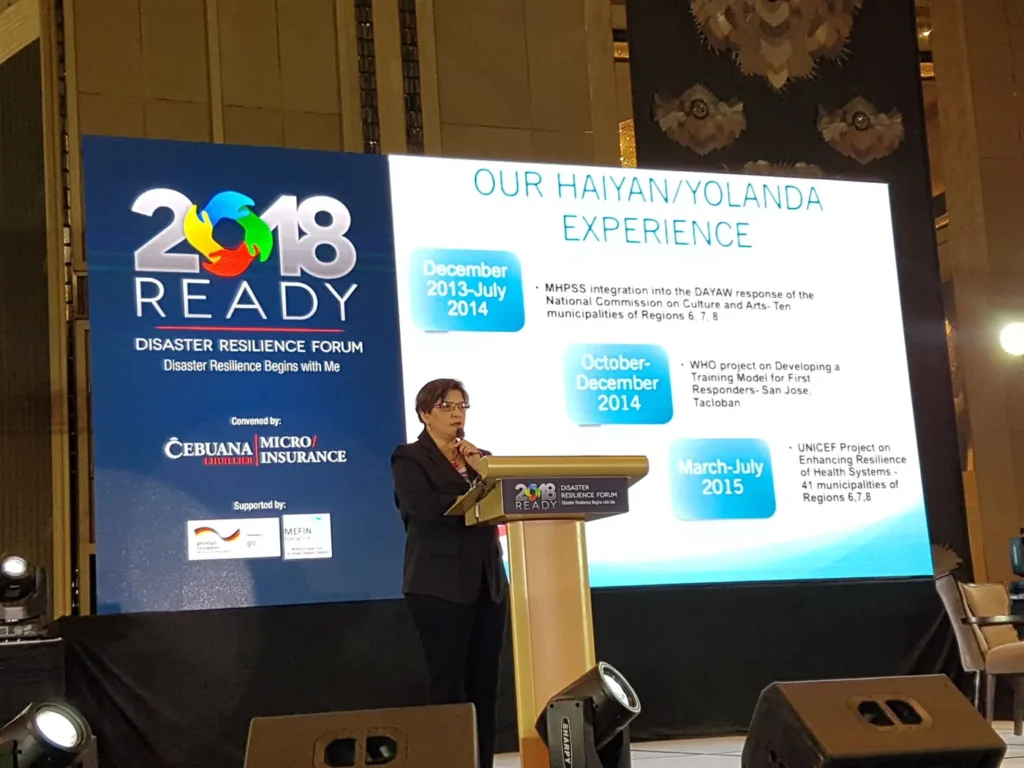

In the recently-concluded Cebuana Lhuillier forum “2018 READY: Disaster Resilience Begins with Me,” Lopez talked about psychosocial support as an effective way to help victims of natural disasters.

Lopez, who is the president and convenor of the psychosocial response center Balik Kalipay, also talked about the center’s humane treatment for disaster victims.

Safe haven

On November 8, 2013, Super Typhoon Yolanda (international name: Haiyan) struck the country, leaving over 6,000 people dead, 28,000 injured, and 1,000 missing. Cost of damages totaled over P95 billion.

Due to the severity and impact of the super typhoon, the World Health Organization estimated over 800,000 cases of mental health conditions among Yolanda victims. (READ: 4 years after Yolanda, trauma still haunts typhoon victims)

Christian Villarino among the victims whose mental health was affected after losing 18 family members, including his parents, to Yolanda.

After becoming a beneficiary of Lopez’s Balik Kalipay, and undergoing the response center’s various forms of therapy, Christian became more sociable and confident, and physically active.

His journey of recovery was shown through a video presentation during Lopez’s talk.

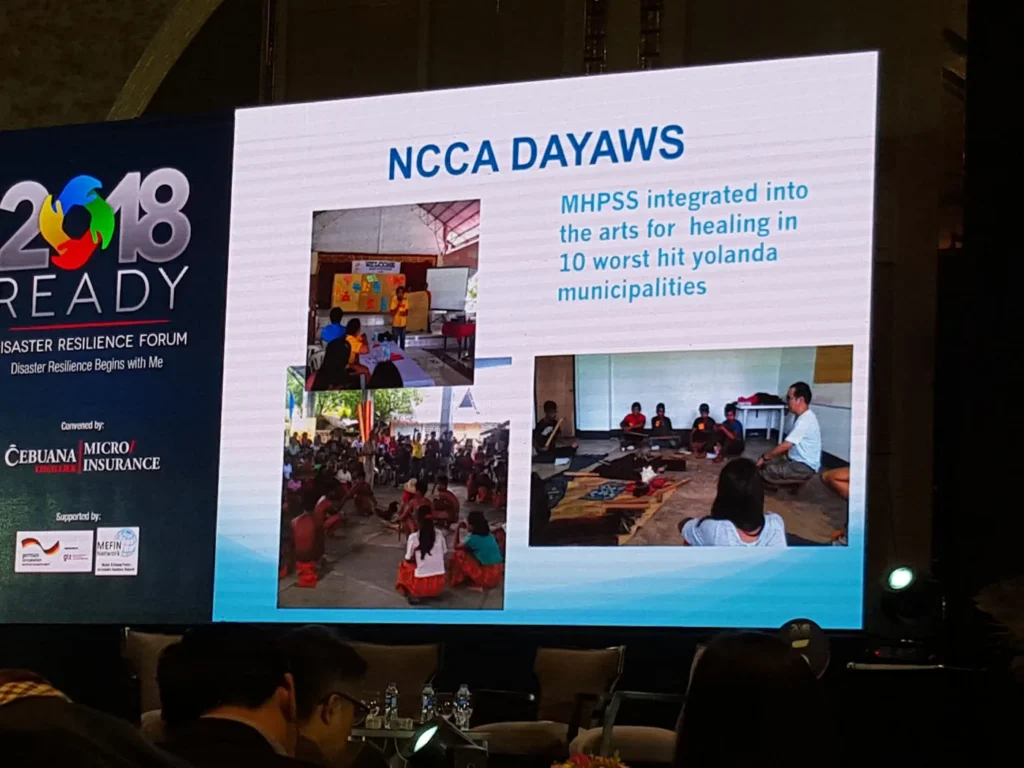

By holding several workshops in partnership with the Philippine Educational Theater Association (PETA) and the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), Balik Kalipay was able to respond to the psychological needs of the Yolanda victims, such as Christian’s.

Beneficiaries undergo different forms of art therapy where they are introduced to a combination of therapeutic and creative activities. Lopez stated that drawing was found to be the easiest and cheapest way to bring out the feelings of the victims.

Lopez cited the importance of training parents and starting on the level of families when confronting child protection in the context of disaster aftermath.

She also observed that children who were affected by Yolanda refused to return to school, became passive and withdrawn, and grew assaultive and aggressive.

“It really is worrisome because you’re talking of a whole generation of Filipinos thinking that life is always going to be difficult, that life has to be something you have to fight for. I think that’s the scariest part of the disasters and emergencies that we have,” she said.

This is why Lopez believes mental health education will strengthen communities in disaster resilience.

“The bottom line is: how do we enhance values, as well as positive thinking, among people who keep on having repeated encounters with disasters?” she asked.

Balik Kalipay does not only focus on victims of disasters. The response center also offers psychosocial processing to caregivers of victims as well as journalists who cover disaster-affected areas.

Heightened awareness

On June 20, President Rodrigo Duterte signed Republic Act 11036, or the Philippine Mental Health Law. The law aims to promote mental health through national policies and programs, while establishing a comprehensive and integrated mental health care system.

Prior to the approval of the measure in both houses of Congress, there were no national systems in place that protected the mentally ill from discrimination.

Lopez criticized how the widespread stigma surrounding mental health can put psychological problems on the back burner.

She described Filipinos as “crisis-oriented “people who don’t immediately act on solving long-term problems.

“‘Pag may tumalon, ‘pag may namatay, diyan lang tayo nagkikilos (We only act when someone jumps, when someone dies),” she said.

Lopez also stressed the need to be more aware of mental health issues and psychosocial problems, given that such complications are “abstract” and harder to spot.

“It’s easy to come up with how many bridges you were able to build, how many buildings were reconstructed,” she explained.

“But how many lives, how many minds, and how many people are suffering psychologically – that’s hard to count. We just have to assume that’s one particular need we cannot be blind to,” she said.

Source: Gaby N. Baizas and Angelica Y. Yang, 5 July 2018, from Rappler